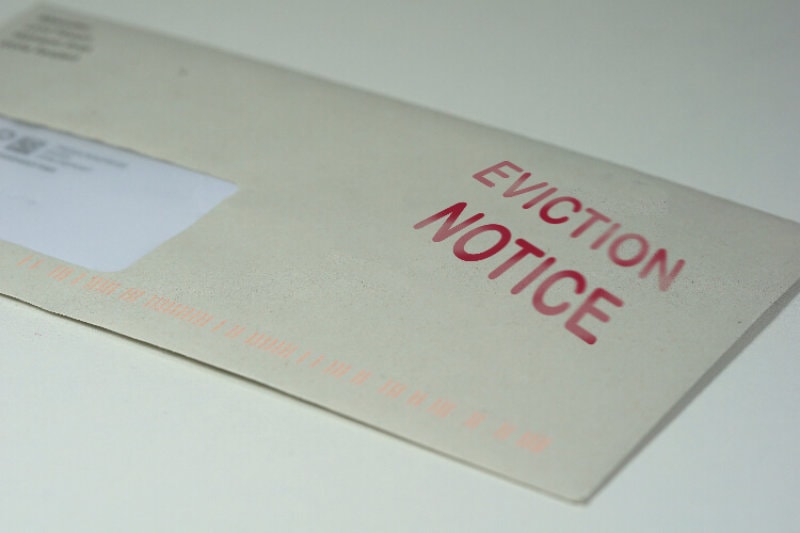

Cities will no longer require or encourage landlords to conduct background checks or evict tenants who have come into contact with law enforcement.

Gov. Gavin Newsom banned these ordinances when he signed Assembly Bill 1418 Oct. 8. Mandatory evictions for contact with a police officer are often part of crime-free housing ordinances, which are in effect in varying degrees across the Inland Empire.

“There is no evidence that these policies do anything to reduce crime. Indeed, a closer look at these policies reveals they are generally motivated by racial animus and a desire to reverse demographic change in a given jurisdiction,” the bill’s author, Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Hawthrone),